I recently read “Creativity – the psychology of discovery and invention”, a fascinating book on creativity written by Professor Csikszentmihaly at Claremont Graduate University. It is based on interviews conducted between 1990 and 1995 with ninety-one individuals who had made a difference to a major domain of culture, the hallmark of creativity. Many of these individuals have been awarded a Nobel Prize or have been recognized in other ways for the contributions they made.

Women were underrepresentated in this sample of creative individuals, as they are in many other situations that implicate leadership. Of the individuals interviewed for the book, about seventy percent were men and thirty percent women. Professor Csikszentmihaly writes “Many women would have liked to become scientists in the 1940s. Why did so few take the opportunity when the doors to graduate training were opened to them?” (p. 47)

I expected Professor Csikszentmihaly to tell us something about the environment in which his creative individuals were embedded, and about how this environment treats creative men and creative women differently. Research abounds on how critical the environment is for how individuals evolve throughout their lives. We know from research about the many stumbling blocks in a woman’s environment that make it difficult for her to follow her heart’s professional passion. Sociologists and economists, to cite but few academic disciplines, have written abundantly about this issue.

It turns out that my expectations were too high. The book stays silent on how the environment in which individuals are situated treats them differently depending on their sex. More importantly, the book is silent on how this differential treatment has implications for how women can follow their professional passions. Yet this point is important if we want to understand creativity and how to foster it.

World War II is one particular environment that Professor Csikszentmihaly considers in women’s ability to live creative lives. During World War II, men were drafted into the army. Universities had empty seats that would, in normal times, have been occupied by men. The very fact that men have to be forced away, through draft, so that women can have a shot at leading creative lives points to the difficulties that women faced in opening just one of the many gates that lead to the land of creativity – higher education. In the 1940s, absent wartime, university lecture halls would have been filled with men. Few women back then received an undergraduate or, much less, a graduate education. Instead, they married and ran households. This is what society expected of them, and this is what society encouraged them to do.

This started with how boys and girls were raised differently, and how schools instilled them with distinct worldviews. Girls were prom queens, forever cheering on the men who were to win. They were not supposed to go to university. Instead, they married young and had children (and birth control was approximative at best before the advent of the pill). If they went to university, the unspoken diploma that was often hoped for was the Mrs. degree. World War II changed this game, because universities stayed empty. They needed students, and so they encouraged women to enroll and stay on. To get a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree or even a PhD.

So, yes, as Professor Csikszentmihaly writes “World War II was especially beneficial for women scientists” (p. 93). But World War II merely opened one of the many gates that women needed to pass through in order to lead creative lives, that is, the gate of higher education. All other gates remained firmly closed. Women were still expected to be wives and mothers before striving for anything else. Women were still facing systemic gender-biases and discrimination when they tried their hand at a profession. This is why so few women took “the opportunity when the doors to graduate training were opened to them” (p. 47). As the saying goes, you can take the woman out of the house (and into the university) but you cannot take the house out of the woman (and how the rest of her environment treats her).

Professor Csikszentmihaly briefly speaks about the challenges that the few creative women he interviewed faced in their private lives. He agrees that “a certain flexbility about gender roles is likely to help” (develop creativity). Yet he does not offer an in-depth discussion how the environment in which women and men were embedded plays an important role in maintaining the gates to creativity closed for women more than for men. I wish he had, because doing so would have told us even more than his rich book already does about the role of the environment in fostering or holding back creativity.

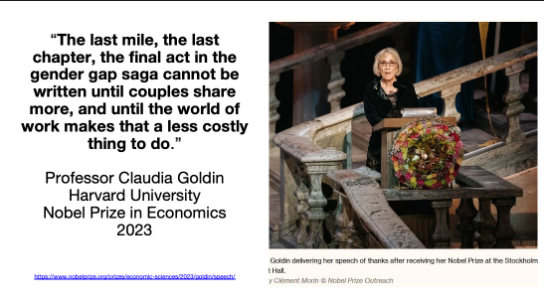

It still is the case, today, nearly 80 years after World War II, that women scientists or women striving to rise to the top of their domain face many obstacles. Close to my professional home, university students will evaluate a woman professor who teaches the same material in the same way as a man professor less favorably than the man professor. When women co-author an academic study with a man, the man receives higher acclaim for the study than the woman.

Being creative requires an environment that nourishes such creativity and that does not throw roadblocks in the way.

Photo adapted from Richard.