A recent study made me think about what gender quotas (and lack thereof) tell us about a woman’s skills. . The study is called “The XX factor: Female managers and innovation in a cross-country setting” and is published in The Leadership Quarterly. It can be accessed here.

It analyzes whether a firm’s new product and service introductions vary with the gender diversity of its employees at different hierarchical levels. Its results show a positive association between new product and service introductions and the presence of women managers. Moreover, this positive association is stronger in countries where firms have a voluntary gender quota and weaker in countries with a legal gender quota.

How do the authors interpret their results?

The study’s authors argue that in countries with voluntary quotas, “women are predominantly selected on the basis of their qualifications”; whereas in countries with legal quotas, “underqualified women may be selected for management positions.” (p. 1)

This interpretation is based on questionable assumptions, as I will argue below, before I propose an alternative interpretation based on my research with women leaders.

The authors explain that if the pool of women managers is small, underqualified women may be appointed in countries with a legal gender quota. In countries without a legal gender quota, a firm’s hand is not forced by the law, and only qualified women make it into management because, as the authors argue, “the selection process is more likely to be based on ability.” (p. 3)

Two problematic assumptions with the authors’ interpretation

Two problematic assumptions underlie this interpretation: (1) there are not enough qualified women for management roles, and (2) selection into management roles is based on merit in ways that do not interfere with gender.

Problematic assumption #1: there are not enough qualified women

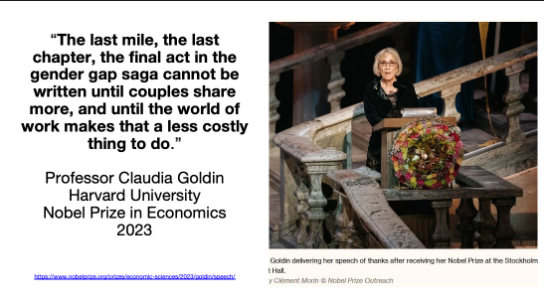

That the first assumption is problematic is shown in a paper that they cite, called “Dynamics of the Gender Gap for Young Professionals in the Financial and Corporate Sectors” by Marianne Bertrand, Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz. These three professors survey graduates from the University of Chicago’s MBA and ask about their professional experience since graduation. They find that, early in their careers, similar percentages of women and men work full-time (89% versus 93% in the year after MBA graduation). However, as their careers progress, women stop working full-time at rates much higher than men. By the 9th year after MBA graduation, 69% of women graduates work full time, compared to 93% of men.

So, yes, the pool of qualified women relative to men shrinks over time. But the shrinkage is not something that it outside of the control of organizations. Instead, it is a direct result of practices and policies within firms. Chief among them are those dealing with role and task assignments, performance evaluation, and promotion and those dealing with accommodations for caregiving (e.g., parental leave).

Problematic assumption #2: selection into management is based on ungendered merit

This brings me to the second problematic assumption: selection into management roles is based on merit in ways that do not interfere with gender. Research shows that, to the contrary, merit and gender are intertwined: role and task assignment, performance evaluation, and promotion are gendered. They are set up and enacted in ways that make it easier for men than for women to advance through the organizational hierarchy and be available when positions in management need filling (Benschop & Doorewaard, 1998; Berdahl, 2007; Castilla, 2012; Ely & Padavic, 2007; Foley & Williamson, 2019; Rhee & Sigler, 2015; Wynn & Correll, 2018).

Women’s relative disadvantage grows when they become mothers: they are dealt the motherhood penalty, which men who become fathers do not face (instead benefitting from the fatherhood premium) (Benard & Correll, 2010). In other words, organizations, by and large, adhere to norms according to which leaders are men and women are caregivers (Mangen, 2021). These norms permeate role and task assignments, performance evaluation, and promotion, which penalize women for not being men.

Merit thus works better for men than women. The more an organization promotes merit, the more men are favoured over women (Castilla & Benard, 2010). Unsurprisingly, over time, fewer women than men end up working full-time. Women are opted out of the workforce.

Organizations contribute to women leaving full-time work

Organizations contribute to women leaving full-time work and the pool of available women being smaller than the pool of available men when positions in management open up. If organizations want to retain the best talent, they need to examine how their practices and policies are gendered and systematically disadvantage and exclude some individuals (i.e., women) while privileging others (i.e., men). But often organizations sidestep such an examination, as illustrated by the persistent gender gap in salaries, occupations and leadership.

Given the smaller pool of available qualified women that organizations can choose from, it is an open question of whether the number of available qualified women are enough to fill open management positions. The answer depends on how many positions are open and need filling and how many women are in the pool of available candidates. The authors show no data to indicate that there are too few qualified women relative to open management positions. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

An alternative interpretation of the results

Now that I have illustrated the two assumptions that the study relies on and how they are problematic, I’ll consider an alternative way of interpreting the study’s results.

My interpretation is grounded in academic studies of gender and organization and my research on organizational leadership. I am currently spearheading an extensive research program on gender inequalities in organizational leadership based on interviews with women leaders across Canada.

Hurdles women face when they climb to the top

Research to date collectively shows how women face hurdles along every stage of their career, more so than men. For example, women are still expected to take on more caregiving work for children than men, which penalizes women because they are not given challenging assignments as they are presumed to be less available for professional work. Women also face double standards during performance evaluation, which means they are less likely to be promoted than men.

In other words, for a woman to make it to a specific hierarchical position, she needs to work very hard to overcome the higher hurdles that she faces compared to men. It is as if she were running a race with obstacles along her trajectory that the men runners do not face. To make it to the finish and come out ahead, she needs to work harder than the other runners and jump over obstacles they do not have to deal with.

Legal quotas even out the playing field

This brings me to my alternative interpretation of the study’s results. To be selected for management positions, women must work very hard, given the hurdles they face throughout their careers.

Legal quotas can be seen as devices for at least somewhat evening out the effects of the hurdles women face, thus balancing the race to the top and making it less unfair to them.

When there are no legal quotas, nothing evens out the effects of the hurdles in women’s careers. Women who make it to the end of the race and win (i.e., they get promoted to management) have to run fast enough while jumping over the obstacles to come out ahead of men who do not have to jump over the same obstacles. These women are extremely good at what they do; they are likely overqualified for the management positions they are promoted to. Unsurprisingly, they perform excessively well in their jobs.

When there are legal quotas, women get reserved some spots in leadership, and they are thus not in competition with men who do not face the same hurdles throughout their careers. The playing field is evened out. Quotas implicitly recognize that organizations are gendered and set up extra hurdles for women that men do not have to face. Because quotas even out the playing field, more women are admitted to leadership roles than when there are no quotas, and overall, women likely are less over-qualified. But they can still be plenty qualified and an excellent fit for the job.

Study needs to acknowledge and discuss systemic disadvantages women face

This way of thinking about quotas is not adopted in the study. The study does not recognize the role of hurdles in penalizing women during the different stages of their careers and creating systemic disadvantages for them.

Most importantly, the study does not recognize how these systematic disadvantages imply that only vastly overqualified women make it to the top when there are no quotas.

Because research on these systemic disadvantages is so rich, the study should be explicit in recognizing the disadvantages and integrating them into explaining its results.

Your thoughts?

References

Benard, S., & Correll, S. J. (2010). Normative Discrimination and the Motherhood Penalty. Gender & Society, 24(5), 616–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210383142

Benschop, Y., & Doorewaard, H. (1998). Covered by Equality: The Gender Subtext of Organizations. Organization Studies, 19(5), 787–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069801900504

Berdahl, J. L. (2007). Harassment Based on Sex: Protecting Social Status in the Context of Gender Hierarchy. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 641–658. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351879

Castilla, E. J. (2012). Gender, Race, and the New (Merit-Based) Employment Relationship. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 51(s1), 528–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2012.00689.x

Castilla, E. J., & Benard, S. (2010). The Paradox of Meritocracy in Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(4), 543–676. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.4.543

Ely, R., & Padavic, I. (2007). A feminist analysis of organizational research on sex differences. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1121–1143. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26585842

Foley, M., & Williamson, S. (2019). Managerial Perspectives on Implicit Bias, Affirmative Action, and Merit. Public Administration Review, 79(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12955

Mangen, C. (2021). “A woman who’s tough, she’s a bitch.” How labels anchored in unconscious bias shape the institution of gender. Women, Gender & Research, 3, 25–42.

Rhee, K. S., & Sigler, T. H. (2015). Untangling the relationship between gender and leadership. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 30(2), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-09-2013-0114

Wynn, A. T., & Correll, S. J. (2018). Combating Gender Bias in Modern Workplaces. In B. J. Risman, C. M. Froyum, & W. J. Scarborough (Eds.), Handbook of the Sociology of Gender (pp. 509–521). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76333-0_37

Photo adapted from Malcolm Slaney.