Earlier this fall, I got the fantastic news of having what I call my pandemic paper accepted in Women, Gender & Research, a peer-reviewed journal from the University of Copenhagen (here is an open access version of the paper). The story of how this paper came to be taught me three important lessons.

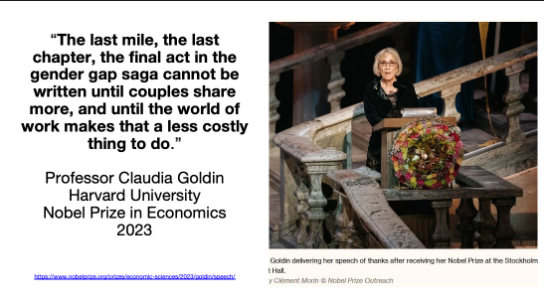

It all started when I attended my last pre-pandemic conference, the Careers Division conference of the Academy of Management in Vienna, Austria, in February 2020. As I talked with one of the participants, she mentioned a call for a special issue of Women, Gender & Research on organizations and unconscious bias. My interest was piqued right away, as I have long been intrigued by unconscious bias. I remember my grad student days when I saw Richard Thaler, who received the Nobel prize for his work on unconscious bias, give a talk on unconscious bias. Years later, I read the book he wrote with Cass Sunstein, Nudge, and I kept up with research on unconscious bias.

Here now was an opportunity for me to contribute to what we know about unconscious bias. I thought back to the women leaders in Canada that I had interviewed in 2017 and 2018. I had read the transcripts of these interviews and had a strong sense that I could learn something from them about unconscious bias. So I decided to go back to my transcripts and reread them, this time looking out for unconscious bias. And if there was something, I was going to submit an abstract to the special issue of Women, Gender & Research.

The abstract was due in April 2020, right after the COVID-19 pandemic got going. At the time, my daughter was four years old and going to public daycare in Montreal. In mid-March, the government in Quebec decided to close all educational institutions, ranging from daycares to universities. My four-year-old was going to be at home, 24/7, seven days a week, as were my partner and me. We were now entering a new experiment: taking care of our four-year-old while attempting to work.

I did submit the abstract, and I was thrilled when, less than a month later, I got invited to submit the full paper by late September. The paper ended up going through two rounds of revisions, the first one of which was major, before being finally accepted in September 2021.

Lesson One: Do Set Priorities

Back in May 2020, when I was invited to submit the full paper, I was working from home with my four-year-old around all day. She still napped in the afternoon for a solid two to three hours. Those were what I call the golden hours where I could do the work that demanded uninterrupted, deep concentration—research. For the rest of the day, when she was awake, my partner and I got organized and took turns being responsible for her. We chopped our working time into one-hour intervals when he or I would plan what she would do and respond to her requests, which four-year-old’s issue a lot. My partner and I shared a home office, so I would hear my daughter reach out for dad during my “off-hour.” Inevitably, we would both be drawn into caring for her.

Given that I need uninterrupted reflection and writing time when I work on heavy-duty research tasks, I planned to do those when my daughter slept, in the afternoon and the evening, after her 8:30 to 9:00 pm bedtime. During her waking hours, I would do administrative work (there is a lot of that) and emails (always too many). This work adapts better to interruptions than research work, as it is easier to get back into the train of thought.

I was not teaching that semester, so I was lucky not to have to shift my teaching from in-person to remote, unlike my colleagues at Concordia University who were teaching and had two weeks to pivot. I have no idea how I would have pulled off teaching remotely, especially since we had just moved into our largely open-space apartment, and I could not use my office at Concordia.

Once I had figured out the best hours to do my research work, I drew up a roadmap of what needed to be done by when for having my paper ready by its due date. I started to block out time in my calendar during those research hours that would be dedicated to the paper. I work best in relatively small chunks of time, ranging from 45 minutes to an hour, that I put in daily (except for weekends, when I do not work unless there is an emergency). I had until late September to produce the full paper, which left me with about four and a half months. I knew that I needed to have a crappy first draft, as I call them, by late August if I was to have an acceptable paper a month later. So I planned backwards from that late August deadline to May and figured out what tasks needed to be completed by when (e.g., rereading interviews; coding interviews; interpreting and grouping codes; theorizing, writing up that crappy first draft).

I knew it would be tight, especially since I had to deal with other research deadlines. But I figured I would try, especially since this could potentially be my first paper on gender inequalities, a subject that, in recent years, had interested me more and more. So I stuck to my schedule, and I got to work.

Lesson Two: Do Ask for Help

The submission deadline for the full paper was late September 2020. This date had been sat in the initial call for submissions for the special issue, well before the pandemic. After the pandemic rolled around, my daily life changed substantially, primarily because I was working full-time from home and caring, along with my partner, for our four-year-old. Of course, this affected my progress on this paper. I was much slower than I usually am. I had tried to anticipate this in my plan, but I had never had to work full-time while caregiving for a small child. It was difficult for me to predict how fast or slow I could work in these new circumstances. It turned out that my plans were optimistic, and I didn’t have the paper ready when late September drew close.

I could have sped the paper up and scrambled throughout the interpretation, conceptualization, and writing. But I was aware that doing so would come with significant risks. First, the quality of my work would suffer. I know how to do my best work: I need regular work spread out over time, which helps me process the research material, think about it, ponder the arguments, revisit the structure. If I speed through this process, it does not play out as well as it otherwise would. Ultimately, the paper loses out and is less strong. Second, I would pay a heavy price from the stress involved in speeding up the paper and taking time from elsewhere for doing so. I did not want to do this to myself. I have tenure, so I am fortunate enough to be able to say opt out of adding more stress than I want to take on.

I decided it was worth a shot to reach out to the editors and ask for an extension. I sat out to write the email where I explained my situation. I decided to ask for a one-month extension, based on the work I had done by that point, how fast I had been able to work, and how much remained to complete. Also, by late September, my daughter was back in full-time daycare (although daycare could close anytime because of COVID).

My request was accepted right away, and to this day, I remain very thankful to the editors for their empathy and accommodation. My daughter’s daycare ran without interruption for all of October (and, in fact, for the whole 2020-2021 academic year), and I was able to submit the full paper by my new deadline.

Lesson Three: Do Let Go

In the final round of revisions, I had three weeks to rewrite the paper while preparing a major external grant application. I decided that two weeks needed to suffice to get the rewriting job done so that I could focus on the grant application, which had its own deadline.

I prepared an Excel worksheet with the reviewers’ comments, grouped similar and related comments together, and brainstormed how to address these comments. Next, I made small notes on how to proceed for each group of comments. Only once I had done this, did I start revising the paper. I began by addressing the most challenging comments first (i.e., contribution-related).

I worked in small but regular intervals and gave myself a deadline four days before my actual deadline to be able to step aside from the paper, let it rest, and give it a last thorough reading with fresh eyes.

I met my deadline and did that final reading, some editing, and then decided to let this work be good enough for resubmission. I should add that school for my now five-year-old was operating, which was very helpful. I resubmitted and touched wood. In late September, I got the acceptance—yeah!

I intend on abiding by my three pandemic lessons. I tend to want to soldier through difficulties by myself and to be a perfectionist. Lessons Two (Do Ask for Help) and Three (Do Let Go) will likely be more of a challenge for me, but if I can stick to them, they stand to help a lot.

I am curious to read how the pandemic has affected your work. What struggles did you face, in research, teaching and administrative work? What lessons did you take away from that?

Photo adapted from Liz West.