In late March this year, I started to think a bit here and there about the funding I had applied for six months ago. The results were due soon, in April, and I began to await them with a mix of suspense (Maybe this time?) and anticipatory defeat (Nah, it won’t happen!).

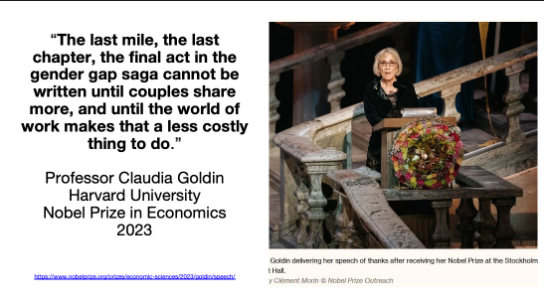

Last fall, I had applied as a principal investigator for an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada for a research program called “Disruptive Dames? The process of disruption underlying women’s transition into organizational leadership.” The program, which explores how gender inequalities in organizations are disrupted over time, is joint work with two colleagues at Concordia University, Professors Joel Bothello and Anne-Marie Croteau.

The Insight Grant programme from SSHRC is very competitive, with a success rate of 32.4%; it is slightly lower in my discipline (i.e., Management, Business, Administrative Studies), where it hovers around 28.2%. Men are granted about 20% more funding than women.

On April 7, 2022, I took a break from my writing to check my emails. I noticed a new message from my university with the (most lovely) subject line “SSHRC Insight Grant Competition Results – good news!” which I opened ASAP. Therein, I was told that “We have just received the SSHRC Insight Grant competition results. I’m very pleased to inform you that SSHRC has offered to fund your proposal.”

I nearly fell out of my chair! I was very (very!) elated.

I contacted the team with whom I had applied for funding to share the good news. I whatsapped with my partner to tell him all about what just happened. I danced in my office. Not necessarily in that order. I was too giddy to now remember.

The victory was all the sweeter since I had unsuccessfully applied last year for funding from the same agency for a slightly different research program. It had taken me quite some time to work through the disappointment I experienced when I learned that I had not received the funding. I had emerged from this process realizing that I did want to apply for funding again and that, for this, I wanted to modify my application substantially. So, last summer, I spent a good chunk of time chopping away at my unsuccessful grant application, re-imagining it in light of the feedback I got from the reviewers, and drafting a new research program.

This is now the third time I have been awarded funding from SSHRC. The first time was in 2008 when I was still an assistant professor. By the second time, in 2017, I was tenured, and the funding was supporting me in exploring what was then a new research area: gender inequalities. Altogether, my three awards have granted me $293,716 for research at Concordia University.

Now, it’s not the case that I have applied only three times for funding from SSHRC and was successful each time. Quite the contrary: since 2007, I have applied a total of nine times, and six of these applications were not successfully (which is roughly equivalent to the overall success rate of 32.4% SSHRC Insight Grant program).

With each funding application, whether successful or not, I learned a bit about what works and what does not, which has enabled me to hone my funding application skills. Below are four lessons.

Lesson 1. Get yourself and the team ready

The challenge of any grant application is to present a compelling research idea. Research ideas don’t fall from the sky. They need to be cultivated, tended to, weeded out and cared for. They need time and attention.

I start thinking about the research idea underlying a grant proposal about six to eight months before the application is due. I generally have some vague idea of what I want to do. I know the broad topic (e.g., gender inequalities in organizations). From there, I need to hone things out, which requires that I consider several factors.

To start, I need to ask myself if I want to do the grant application alone or with others. I prefer to work with others. I try to choose people whose work style I know well enough to be reasonably confident we are a good fit and work well together. I approach them to gather their interest in joining a team for a grant application, and, if there is interest, I set up a meeting. During the meeting, we share our takes on the broad topic and what aspect of it each one of us would like to work on, given our own research agendas..

We then have a couple more meetings, usually spaced about three to four weeks apart, to hone out the work each want to do. Doing this kind of homework enables us to get invested in the application and see ourselves and our research agendas in it. It also helps ensure that the grant application will eventually read like a research program from a team instead of a couple of different research projects hobbled together last-minute by various researchers.

In this process, I also need to get a good idea of where I want to go with the grant application. How does it fit into my research agenda and professional plan? Is it for research in a new area that I want to integrate into my research agenda to broaden it? Is it research in an area where I have already published, and that deepens my research agenda? I need to be clear on this to know how to see and envision my role in the project. Clarity will also help during the write-up of the application because funding agencies often need to see how a research project fits into the research agenda of the individual applicants.

Getting clarity requires some soul searching and perhaps a five-year plan. The Professor Is In has excellent advice on five-year plans. Planning needs to happen anyways for most grant application. They often require multi-year budgets for how the funds would be spent and timelines for how the project would be executed. I find it helpful to situate the grant application within the broader plan for my research, as reflected in my five-year plan. Doing so enables me to figure out how much time I will realistically be able to dedicate to the project and what adjustments, if any, I need to make to my other research, given the project proposed in the grant application.

Lesson 2. Learn from others

The time comes to write up the grant application. I usually start the write-up about three months before the application due date. Funding agencies and universities can have different deadlines for the same grant application. At my university, the internal deadline for applying is generally about ten days to two weeks before the agency deadline. I note these deadlines (and have Google Calendar send me reminders).

I check the funding agency’s website for the requirements and recommendations regarding the grant application. What is expected in terms of its structure? What are the necessary building blocks of the application? For example, what headings are expected? Who is involved in evaluating the application, and what knowledge do they have? How much field-specific jargon can I use in the writing (in my experience, less is more)?

I also turn to prior grant applications that received funding from the same agency. At my university, the research office collects successful applications. I read some applications, being attentive to those reminiscent of my own, still vague research program (e.g., in terms of methodology, theoretical positioning, data).

I am careful to note how successful past applications are structured and how their different building blocks are linked. For instance, how is the question underlying the research program introduced? Where does the application discuss the problem in the literature that the research program seeks to address?

I pay attention to the writing. How different is the application from the academic writing that I do when I publish? How much does the description draw on specialized field-specific terms versus general expressions? How is the problem in the literature described?

Finally, I go back to my previous grant applications, especially if they were dealing with a related research program, and carefully review the comments I received from assessors and evaluators. Comments help shed light on issues with unsuccessful applications that I overlooked simply because I was too close to the material. I make sure to understand the issues raised in the comments and address them in my new grant application.

Lesson 3. Know thyself

Over the years, I have learned how I work best in ways that help me accomplish my goals while maintaining a healthy work-life balance. (I try to focus my goals on deliverables that I control, like submitting a paper to a journal, not outcomes that I don’t control, like getting an article accepted for publication.)

I need structure. I have realized this from trying, for a long time, to get work done without structure. I would just take on projects and then fit the work they needed between my other obligations like teaching and service. This approach left me frustrated because I felt like I was always chasing my work and not in charge of it. I got lost within the many demands that emanate from my academic environment where I wear lots of different hats (e.g., researcher, supervisor, teacher). This environment constantly makes demands on me, and if I do not have a structure within which I can situate the demands (and choose the time and place to deal with them), they gobble me up, much like a person can get sucked into quicksands.

Then academic podcasts happened. I stumbled across several podcasts, often run by academics or former academics who also coach. They put words on my experiences and made me realize that I lacked structure. Structure with a small “s” (e.g., How do I get work on a project done on a daily basis to meet a deadline?) and with a big “S” (e.g., What projects do I want to take on? Where do I see myself in five years?).

I embraced structure. Doing so has enabled me to be decisive: I decide what I want to do in the long run and how I translate these goals into the medium and short term. Structure helps me achieve my goals and enjoy the process of working towards them.

We are all different, though, and we all need to figure out what we need to do our work. Perhaps structure is your thing too, or maybe it isn’t. Go and find out.

Lesson 4. Build in resilience

The best-laid plans are meant to go awry. Because life happens. It is essential to consider the inherent messiness of life when planning a grant application. Not doing so means running the risk of missing the submission deadline or handing in a half-polished application.

In practice, I give myself plenty of time. I budget extra time ahead of deadlines.

For example, I like to give the grant application to read to the person in my university who handles external funding to get the feedback from someone who is used to seeing grant applications but does not work in my field or even is a researcher. This helps me understand how well the application reads and what is unclear. I plan to have the grant application finalized about a week before I should give it to this person. Usually, something comes up (e.g., a revision deadline for a paper, a sick child), and I manage to finalize the grant application just in time to give the grant application to this person.

Your thoughts?

Photo adapted from “Money” by Pictures Of Money under Creative Commons License CCBY 2.0