Recently, I read that women and men are equal in Canada when it comes to the law. This diagnosis comes from a solid source: the 2024 edition of the Women Business and Law database (WLB) from the World Bank. The database measures gender inequalities in laws across different countries for eight areas that the law deals with, such as mobility, workplaces, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pension.

In having gender-equal laws, Canada is in exclusive company: many countries do not achieve legal gender equality. For example, our southern neighbour, the US, receives a less-than-perfect score from the World Bank, failing to deliver gender-equal laws in three legal areas: pay, parenthood and pension.

Yet, despite Canada’s laws, we know that when it comes to gender equality, we’re not quite there yet. There is a difference between what the law says and how we live. A series of reports from various sources, including Statistics Canada, show that gender inequalities remain persistent across different facets of life in Canada, including corporate boards. A 2023 report from Osler, a Canadian law firm, tells us that most corporate board members remain men: women comprise 26% of corporate directors.

What is the missing link between our gender equal laws and gender inequality on corporate boards? I argue that a central missing link is social norms, which I also call soft laws.

Social norms are collective values and unofficial rules of ideal conduct that guide our behaviour. There are two types of norms: prescriptive and descriptive. Prescriptive social norms tell us what we should do and how we should do it. Should a woman strive for a leadership role in a corporation? How should she behave as she works? Prescriptive social norms offer answers to these kinds of questions. In contrast, descriptive social norms are concerned not with what we ought to do but with what we actually do. What kind of work do women do? How do they behave? Descriptive social norms answer these questions via stereotypes, which are widely held oversimplified generalizations of specific groups of individuals, such as women.

Social norms in Canada remain profoundly gendered. A 2018 IPSOS poll reveals a large difference between what Canadians value in a woman and what they appreciate in a man. Men are valued for ambition, leadership, and strength. Women are valued for different attributes: looks, family orientation, and intelligence.

Social norms matter because they shape how we think, which happens instantaneously, as I explain in a study on unconscious bias. When we see somebody, our brains immediately draw on their looks, comparing them to norms we have internalized throughout our lives and assigning them to a gender category. This comparison process has implications for how we react to people, how we speak, and what we do. When our social norms are gendered, we respond differently to women and men and interact differently with them.

Social norms also come into play when we look at leadership. The norm for women is to be communal and focus on others. An excellent example of this communal norm is a woman with a child. As a mother, she is expected to take care of her child and center her activities on the child. For men, the norm is different. Men are expected to be agentic and focus on themselves. A good example of an agentic role is a man who is a leader, like a CEO. As a leader, he is expected to be rational, assertive and controlling.

Because more men than women are leaders, leadership remains associated chiefly with men rather than women. In other words, leadership is primarily viewed as being masculine in a particular way: the masculinity associated with leadership is agentic. In other words, the kind of man who is seen as a leader is someone who focuses on themselves, asserts their needs and controls others. He is not expected to act communally and focus on others. The agency norm associated with leadership has implications for women who are or want to become leaders. They are between a rock and a hard place. I have researched what happens when women leaders deal with norms around how they should be and act, and I have found that these norms are often problematic for them in two ways.

First, women leaders face a conflict between their leadership roles, which require agency, and their caregiver roles. Women are still largely seen as those who are caregivers for their families, including for their children. This caregiver role requires that women are communal, which is inconsistent with leadership. Accordingly, a woman who is a leader or wants to be a leader can be delegitimized in the leadership role because the aura of caregiving remains attached to her (because of her gender). To compensate for this delegitimization and be taken seriously in a leadership role, she has to work very hard. Many women leaders I interviewed told me they had to work harder than their men peers to get where they are.

The problem is not the women. The problem is how we think and talk about leadership. Leadership is still largely refined around agentic behaviour that focuses on the self, competition, and aggression, which doesn’t leave much room for communal practices concerned with the well-being of others.

This brings us to the second problem women leaders face when they deal with norms around how they should be and act. As I just pointed out, norms around leadership remain anchored in agency without making room for communal practices. An implication of this is that it is difficult for men who wish to be seen as having leadership potential to engage in caregiving work. In other words, men can be leaders or caregivers, but not both. Norms around leadership discourage men from doing carework. And so it’s often women who pick up the carework when men feel they don’t have a choice. Women, then, do not have a choice either because carework needs to be done by someone.

Suppose we want to address the problem of how norms, especially norms around leadership, make it hard for women to get into leadership roles. We would then act on how leadership is defined and perceived in ways that discourage men from doing caregiving work. We would have to act on how men can behave vis-a-vis their family and friends, and we have to enable men to take on caregiving behaviour.

The problem arising from norms around leadership that define leadership in restrictive ways, in particular as excluding caregiving, is relevant not just for mitigating gender inequalities but also for addressing other critical challenges we currently face, notably climate change and employee burnout.

Corporations can operate under an exploitative worldview where the world is there for them to take advantage of. Examples of such exploitative practices include pollution and resource extraction (e.g., in oil and gas). Exploitative activities are not sustainable (because eventually, the world runs out of non-renewable natural resources) and contribute to climate change. Other exploitative practices include how corporations treat their employees, who are often burned out, as I write in The Conversation, because they are worked to the point of breaking. Here, a caregiving perspective would help address exploitative practices because corporations wouldn’t approach the environment or their employees as theirs for the taking but from the perspective of taking care of them. Taking a broader perspective beyond agentic behaviour and including caregiving behaviour in how we define and think about leadership would help address these issues.

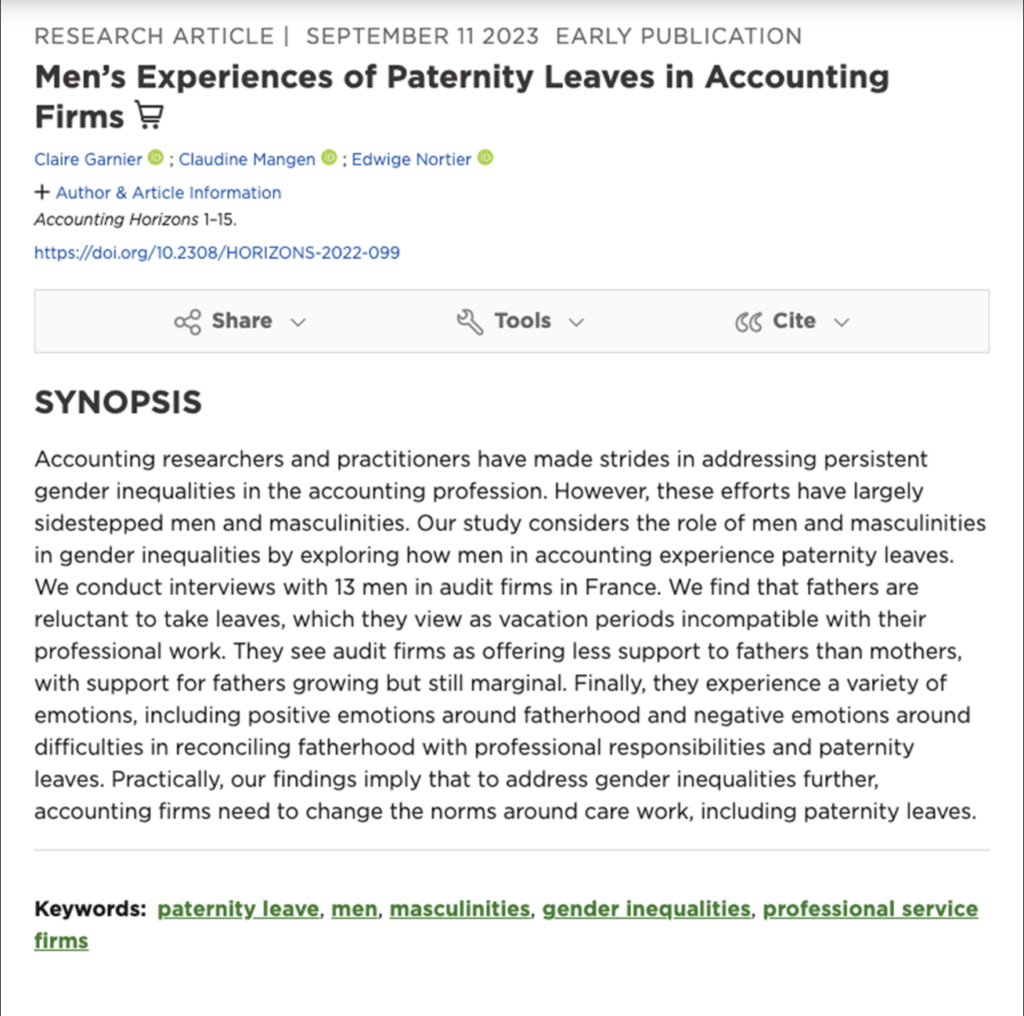

Now, let’s go back to caregiving. I have started to do research in the area of caregiving and how it is perceived and done by men. This research is based on interviews with men in a country where, as in Canada, women and men are equal as far as the law is concerned: France. Moreover, the men interviewed were professionals working in accountancy and, thus, highly ambitious. In those two aspects, these interviewees are similar to people who want to get on boards in Canada.

The interviews with men working in the accountancy profession in France enabled me and my co-researchers (Claire Garnier from Kedge Business School in Bordeaux and Edwige Nortier from EM Lyon) to shed light on paternity leaves. Did working fathers take paternity leaves? What were their experiences with leaves? How did they feel about leaves?

Our study, now published in Accounting Horizons, showed four critical findings for our understanding of men, work, and care.

First, fathers working in the accountancy profession in France are extremely reluctant to take the paternity leave they are legally entitled to.

Second, working fathers often see paternity leaves as times of vacation rather than periods during which they actually care for their babies. Working fathers usually consider that paternity leaves are incompatible with professional work.

Third, the organizations these fathers work for do not treat them as they treat working mothers. The organizations encourage working mothers to take maternity leave more than they encourage working fathers to take paternity leave. Organizations are generally more accommodating towards working mothers than working fathers via programs specifically catered to working mothers.

Fourth and last, working fathers do not necessarily like this state of affairs. Many of them, especially younger men, expressed frustration with how things were and wished it would be more acceptable for them to take paternity leave.

In conclusion, my discussion has highlighted how norms around leadership and women’s and men’s behaviour contribute to persistent gender inequalities. If we’re going to make progress in addressing gender inequalities, we need to change these norms around leadership and the behaviour of women and men. In particular, we need to enact change in organizations in how we talk about and do care. When it comes to care, organizations need to include men; we must have good role models who show how men can enact caregiving behaviour.

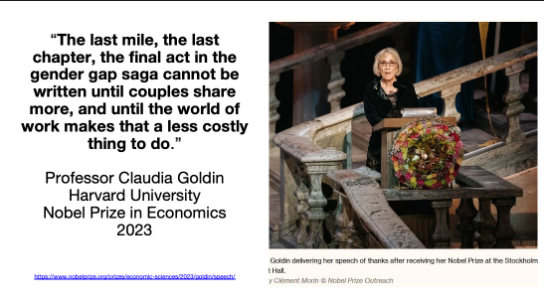

I will close with a quote from last year’s Nobel Prize winner, Professor Claudia Goldin from Harvard University, who has done extensive research on gender inequalities.

Your thoughts?